I recently had the chance fulfill a long-time ambition, to have a chat with the Richard Louv best-selling author of many books, including “Last Child in the Woods” and “The Nature Principle.” Richard is a leader in thinking about nature deficit and our need to connect to the natural world, especially at a young age. We recently interviewed Richard for our our show “Love Nature: the Biophilia Podcast.”

…the Nature Principle suggests that, in an age of rapid environmental, economic, and social transformation, the future will below to the nature-smart – those individuals, families, businesses, and political leaders who develop a deeper understanding of nature, and who balance the virtual with the real. – The Nature Principle 2012, p. 4.

My co-host Dr. Dan Dombrowski and I talked to Richard about his latest book “Our Wild Calling” (2019). In it asks people of many different backgrounds to talk about their specific relationship with animals. There is marine biologist Paul Dayton’s close call with a giant octopus, New Zealand-based professor of ecology Charles Daugherty’s special relationship with the ancient “living fossil” reptile, the tuatara. Richard also talks with special affection about his own adventures with his childhood pet, a collie named Banner.

It’s a wonderful read – I highly recommend it. It’s easy to identify with the many ways his interviewees respond to other life forms: sometimes fear, sometimes warmth, always with curiosity or fascination. I am probably like many readers in that the book made me think about my own encounters with – and relationships to – animals, wild and otherwise. I’ve been fortunate to have had animals as part of my daily existence for most of my life, both at home and in the field. From the many pets and and small livestock I kept growing up to a Master’s studying porpoises in Central California’s Monterey Bay and a PhD working with Australian waterbirds, to working now at an institution (North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences) that keeps and displays live animals, I have had the good fortune to be up close to a great many. Much of what has inspired me has been finding ways to decode their behaviors in response to what’s happening in their environment.

Something that has struck me is the amount of time many animals spend not particularly doing anything, or doing something apparently for the sheer pleasure of it. One particularly memorable time was on Monterey Bay, where I was learning to SCUBA dive as part of my postgraduate course in marine biology. I was sitting in a Zodiac with the instructor and a couple of other students, learning how keep from getting tangled in giant kelp as you move through it. Just to my side, a harbor seal popped up and lay on its back in the water. It was within easy reach, so I started scratching its belly as you would a pet dog. I can still remember its taut, cigar of a body stretched over a layer of think blubber insulating it from the cold water. Its wet spotted fur was short and dense and, as I rubbed it, I could see its white skin appear beneath. The seal closed its eyes and contentedly folded its front paws up on its chest. It stayed there until we jumped in the water, where the ocean was teeming with seals, sea lions and otters (one of which latched onto the fin of my dive buddy).

Once I open the box of memories, so many seemingly pointless animal behaviors come to mind. By “pointless,” I mean that they have no obvious benefit to survival (“adaptive significance,” in bio-speak). The baby sea lion that pulled a prank on me when I leaned over a boat into the water. Dolphins and an orangutan who taught me games to play with them. A crow fascinated by a feather it had just molted. Science is quick to say that animal play, especially in the young, is honing skills required for survival and reproduction as adults. The idea that animals could be doing something just because they like to do it, seems perhaps a little too close for comfort. Richard Louv makes this point when he cites Descartes, whose view was that nonhuman animals are like machines, without thoughts, reason, or souls like human animals and as such cannot be categorized with humans.

Today, we have what I think is a muddled view of animals. None of us who has ever had a dog, cat or parrot as part of our family would liken them to machines. They are too individualistic. They assess us and, at times, manipulate us. Frequently, they express simple joy at being in our company. However, while we acknowledge the specialness of individual animals, society is largely content with the plight of battery hens and feed-lot cattle. Collectively, we ignore the precipitous decline (and, in the case of the Northern White Rhino, extinction) of African megafauna from the illicit wildlife trade. We turn a blind eye to the slaughter of marine mammals as part of traditional harvests and the catastrophic loss of wildlife habitats around the globe. Can can our feelings about individual animals give rise to caring more about the environment?

Richard Louv discusses forming deep connections to nature at a young age as a foundation for stewarding the planet. This resonates with E. O. Wilson’s 1984 book Biophilia. In it, Wilson contends that humans have an innate desire to affiliate with other life forms. To this list, I would argue a third as a related argument for environmental stewardship: animal awareness. If animals are aware self-aware, if they can think and interact to their circumstances on an emotional level more or less as we do, of they know who they are, then does that add another dimension to how we treat them and their environment? If animals can process what’s happening to them as individuals, does it add further complexity to harvesting long-finned pilot whales in the Faroe Islands or to the annual poaching of 12,000 turquoise-fronted Amazon parrot nestlings from Brazilian forests, bound for the illegal pet trade?

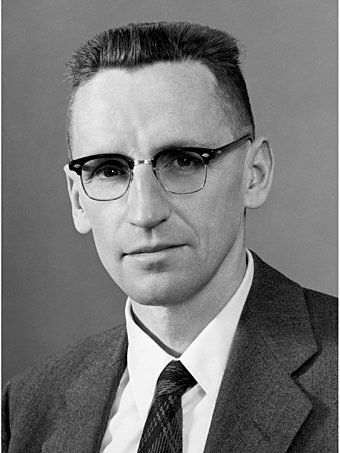

Observations of complex behaviors play have led some behaviorists to look beyond a Cartesian paradigm to study self-awareness in animals. One researcher who explored this in detail was Donald Griffin (who died in 2003 – frustrated that I never got to him) author of a number of books, including Animal Minds: Beyond Cognition to Consciousness (2001). In it, he reviews the state of knowledge and its philosophical and ethical implications, concluding that animals are, indeed, conscious and aware of themselves and their relationship to their surroundings. He was not the first person to give this subject attention. Margaret Washburn (1871–1939) conducted experiments over the course of decades on unpacking what may drive the animal mind. Like Griffin, she maintained that the minds of non-human animals could be inferred from their behavior, based on the analogy of human conscious experience, and that animals could think and cared what happens to them and to their environment. Even Charles Darwin devised experiments to study something akin to intelligence in earthworms.

Perhaps Douglas Adams described best why we haven’t evidence animal awareness better. It could be that our our own internal biases about the nature of intelligence make it too difficult to observe clearly: “For instance, on the planet Earth, man had always assumed that he was more intelligent than dolphins because he had achieved so much—the wheel, New York, wars and so on—whilst all the dolphins had ever done was muck about in the water having a good time. But conversely, the dolphins had always believed that they were far more intelligent than man—for precisely the same reasons.” Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker‘s Guide to the Galaxy (1979).

For the benefit of our future on Planet Earth, we urgently need tools to support a rationale for caring for the environment. Whether it be biophilia, nature deficit disorder, animal awareness, environmental goods and services, the Sixth Extinction, the Anthropocene, or something entirely new, these tools must unlock a new way of looking at the world, and our place on it.

Thanks Eric for another compelling blog. “Mind” is a fraught concept as is “intelligence”. Monty Python noted, “… pray that there’s intelligent life somewhere up in space/ ‘Cause there’s bugger all down here on Earth.” I guess they weren’t speaking on behalf of dolphins and kea. Meanwhile back in Whanganui, we are still working on elaborating The River is a Being concept (Te Awa Tupua), and out at Tarapuruhi/ Bushy Park I am learning every day more about the mauri (life force) of the forest- as a whole. It displays an intelligence in its self-regulating, self-repairing exuberance. Perhaps the species present are interwoven trains of thought in this exuberant ecosystem “mind’. If you don’t mind my non-Cartesian ideas.

Thanks for your thoughtful response, Keith! Yeah, Kea redefine intellect on their own terms I think. And the Whanganui River remains a major triumph of forward thinking legislation, cited the world over. Very exciting time and place to be/have been. Interesting to ponder whether it is sentient. Some interesting thinking coming, oddly, from partial physics.