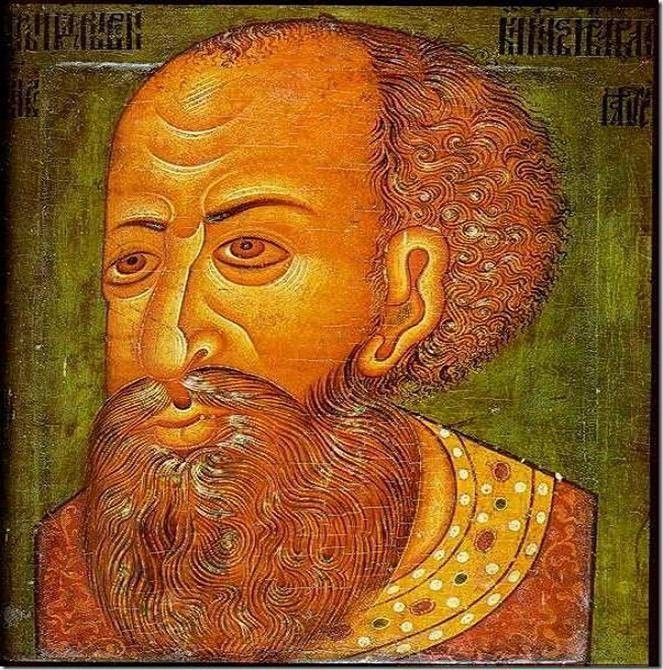

In my earlier Bad Leaders posts, I have written about Caligula, Vlad the Impaler, and Henry VIII. Each offers a different failure mode of power. Caligula collapsed into theatrical narcissism. Vlad ruled through terror shaped by perpetual threat. Henry governed as though appetite were policy. Ivan IV of Russia belongs in this company, but for a different reason. He represents the slow conversion of fear into absolutism, and the damage that follows when personal psychology becomes state doctrine.

It is worth beginning with language. “Terrible” did not mean what it means now. In Ivan’s time, the word carried the sense of awe, dread, and overwhelming force. Something terrible inspired fear because it was vast and uncontrollable. Ivan was not nicknamed for cruelty alone. He was feared as an elemental presence, unpredictable and consuming. That distinction matters, because it points us away from caricature and toward structure.

Ivan’s early life offers no mystery. His father died when he was three. His mother died when he was eight, likely poisoned. The boyars who governed in his name abused him, neglected him, and murdered rivals openly within the palace. Contemporary accounts describe a child who learned early that survival required vigilance, secrecy, and emotional withdrawal. Modern psychology would not struggle to recognize the ingredients for paranoia and narcissistic compensation.

When Ivan took power, his early reign was competent. He introduced legal reforms, strengthened central administration, and expanded Russian territory. These achievements matter, because they make his later collapse a leadership failure rather than an inevitability. Ivan did not begin as a madman. He became one through isolation, suspicion, and the progressive removal of constraint.

Frightening Use of Power

The turning point came with the creation of the Oprichnina. This went beyond being a policing force, becoming an institutionalization of Ivan’s inner life. Loyalty replaced law. Fear replaced governance. Anyone could become an enemy, and evidence became irrelevant. Entire towns were destroyed not because they rebelled, but because Ivan suspected they might. This is where leadership failed decisively. A ruler who cannot tolerate ambiguity will always default to violence, because violence resolves uncertainty quickly.

about 1872. The courtier of in the foreground stands condemned with no trial, while the other courtiers look nervously on.

The consequences were disastrous. The economy collapsed as land was confiscated and populations displaced. Agricultural output fell, famine followed, and depopulation accelerated. Military campaigns drained resources without delivering durable security. Ivan’s infamous killing of his own son was not an aberration. It was the logical outcome of a system in which power was personal, unchecked, and emotionally reactive.

This is where Ivan aligns most closely with Caligula. Both men treated the state as an extension of self. Dissent became betrayal. Criticism became treason. Reality itself became negotiable. Unlike Henry VIII, whose excesses were buffered by institutional continuity, Ivan dismantled the very structures that might have limited his damage. Unlike Vlad, whose brutality operated within a coherent external threat, Ivan turned inward and consumed his own society.

From a leadership perspective, the pattern is clear. Absolute power does not merely permit cruelty. It amplifies cognitive distortions. Paranoia thrives in environments without feedback. Narcissism flourishes when accountability disappears. Totalitarianism emerges not from ideology alone, but from fear combined with authority.

Wounded Psyche and Unlimited Power

Ivan believed himself chosen by God, uniquely responsible for the fate of Russia. That belief justified everything. It also isolated him completely. By the end of his reign, Russia was weaker, poorer, and traumatized. His policies created the very instability he feared. His dynasty collapsed into the Time of Troubles almost immediately after his death.

Ivan IV remains compelling as an example of poor leadership not because he was uniquely evil, but because he was frighteningly human. He shows how a wounded psyche, once armed with unlimited power, can reshape an entire nation in its own image. The lesson is structural. Leadership without constraint becomes pathological.

If there is a fictional analogue here, it is Palpatine, a figure who understands institutions well enough to hollow them out, who feeds fear until it demands obedience, and who mistakes control for stability. Ivan did not burn the world for pleasure. He dismantled it in the name of security.

That is what makes him a genuinely bad leader. Not spectacle or cruelty alone, but the conversion of personal fear into national catastrophe.

Leave a comment