At the Linda Hall Library, in Kansas City, we’re proud of our prodigious History of Science collection, which dates back to 1472. There’s little more engrossing for a lover of books or history than, with hands newly washed, leafing through these books and imagining the people who handled them over the centuries, learned from their contents, and enjoyed their often lavish illustrations. When they were first published, these books sat at the edge of knowledge. Their authors used the best tools of their time, pushed at the limits of what was then known, and sometimes stepped beyond their boundaries. At the moment of publication, these works were modern, even daring, and occasionally controversial. Each page was an act of ambition or perhaps prescience, creating a platform for what was to come.

Now they are part of our collective past. We turn their pages in the History of Science Reading Room and see the past, yet the ideas inside their covers are part of a momentum onto which is still being added today. Some seeded discoveries that would truly arrive only hundreds of years later. And that unbroken line provokes questions that have not yet been answered. The distance between their time and ours sharpens the view of how knowledge is created, changes, and endures.

To illustrate, I’ve chosen three books from our collection that are personal favorites, of the hundreds that would make great examples. Each book, while very different, shares the fact that they marked the frontier of science that has been built on ever since. Each exemplifies a sense of passionate inquiry that shattered paradigms in which they were created.

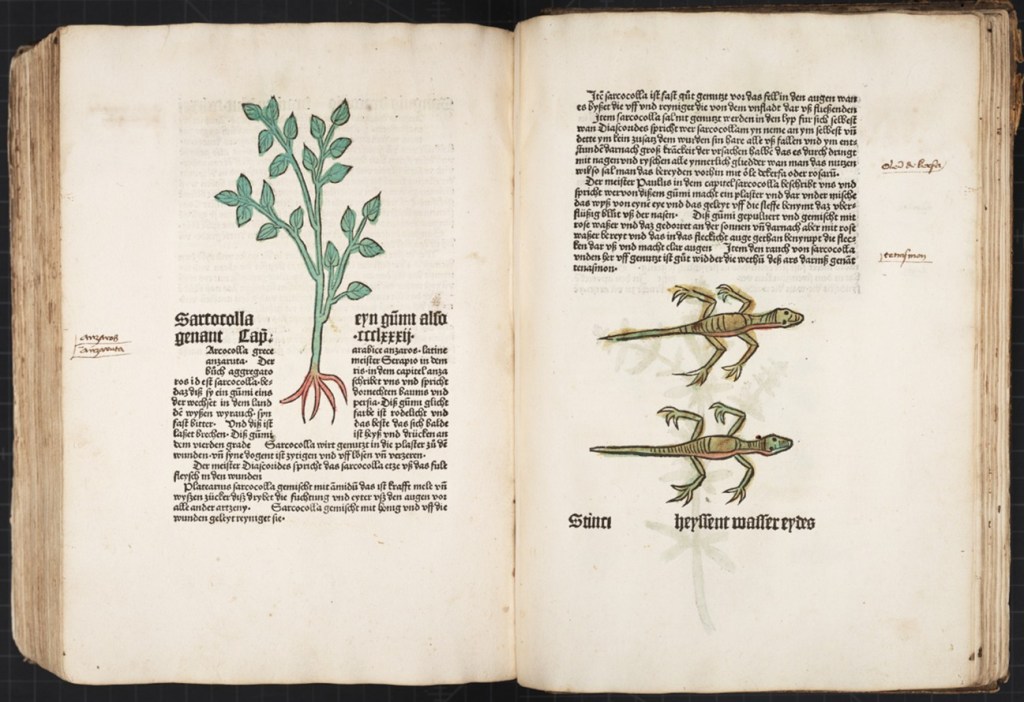

Peter Schoeffer’s Gart der Gesundheit (1485) – Medicine, Myth, and the Roots of Pharmacology

When Gart der Gesundheit (Garden of Health) appeared in Mainz in 1485, it marked a turning point in the accessibility of knowledge. Earlier herbals were circulated in costly manuscripts, usually in Latin for elite scholars and the nobility. This was the first printed encyclopedia of medicinal plants in the German language, making it accessible to physicians and to a growing lay audience. Its woodcut illustrations provided authority, offering recognizable images of plants and animals to readers who either might never encounter them directly, or who might not have practice knowledge to distinguish them apart.

The book’s blend of accurate observation and fabulous invention captures the transition from folk knowledge to the beginnings of scientific observation. Basilisks and dragons appear in the same volume as fennel and peppermint, each described with the same exacting detail. Some remedies are fanciful, others prescient, and together they reflect the earliest stirrings of what we now call pharmacology. The modern search for plant-derived medicines, from aspirin to cancer drugs, follows a path first laid down in works like this one.

The particular page open has to do with afflictions of the eye. While names have changed, it seems most likely that the plant on the left is Persian Gum Astragalus sarcocolla, used for its resin, and the “water lizard” on the right is the common newt Lissotriton vulgaris, which was more associated with its moist skin and habitat that any real utility.

While many of the medical practices in Gart der Gesundheit were completely wrong, and quite a few even dangerous, the book served to expand the reach of medical knowledge by moving from manuscript to print. For the first time, physicians and lay readers alike could consult the same illustrated compendium in their own language. Its woodcuts gave recognition to plants and animals that many readers would never encounter in person. This book established a model of systematic classification and communication that later herbals and pharmacopoeias continued to develop. Modern pharmacology still follows that impulse to link natural forms with healing. This book appears in The Grandeur of Life , an online exhibition on the Library website.

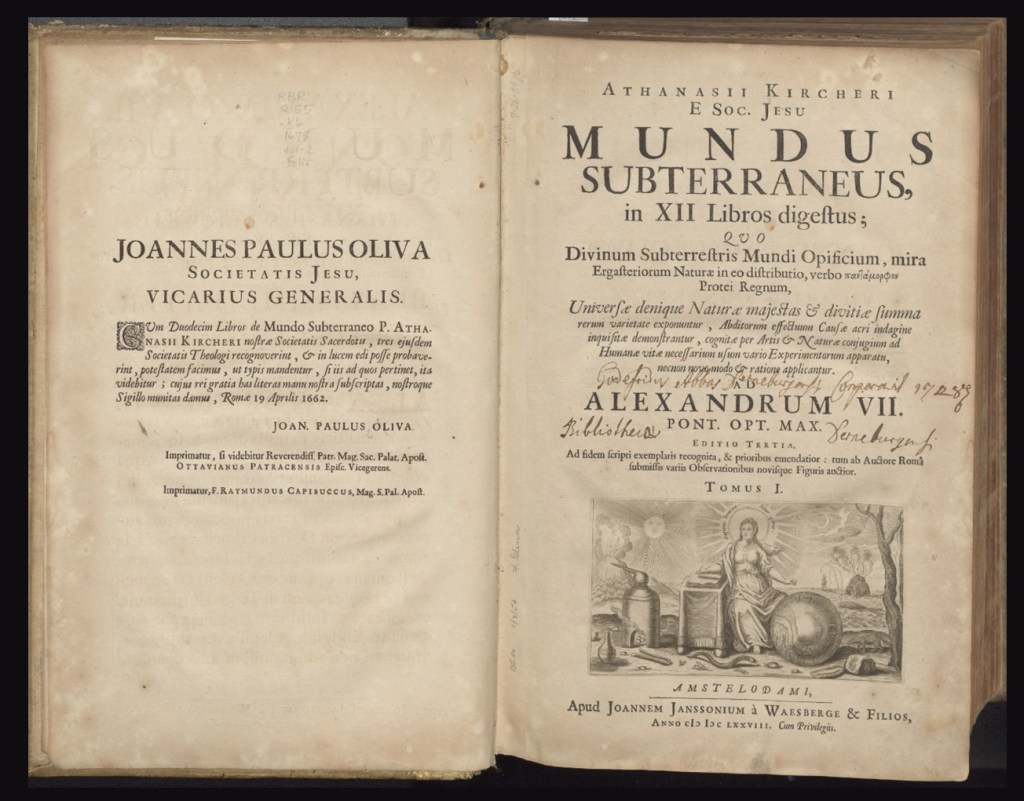

Athanasius Kircher’s Mundus Subterraneus (1665) – Mapping the Invisible Earth

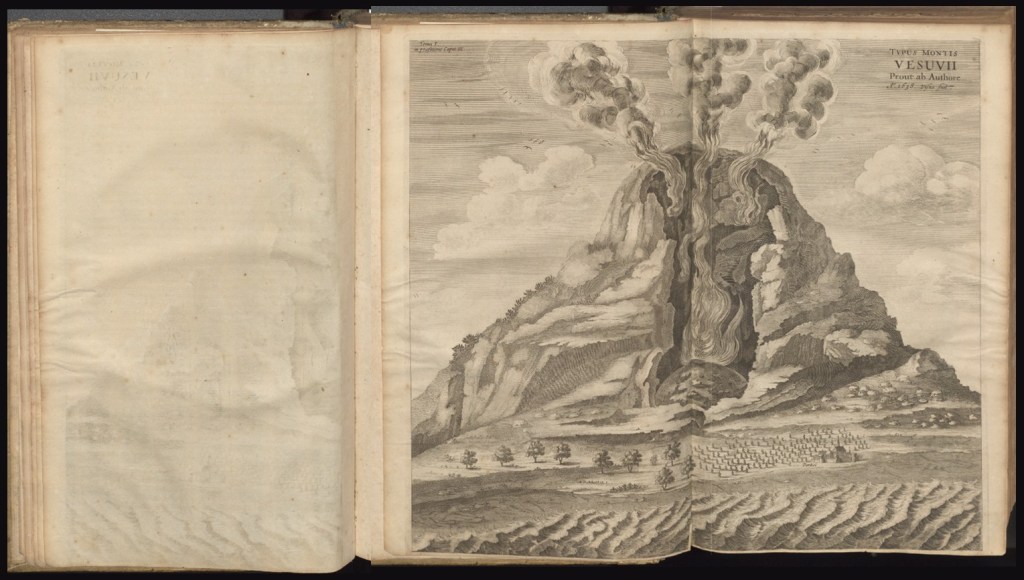

Kircher, a Jesuit polymath often called “the last man who knew everything,” devoted his life to explaining the hidden workings of the world. In Mundus Subterraneus, he proposed a grand synthesis of geology. He imagined the Earth as a living body with underground arteries of water and fire, its volcanoes linked by fiery channels to a blazing core.

Though many of his claims were mistaken, the scale of his ambition was extraordinary. At a time when geology was a descriptive science, Kircher sought unifying principles that tied distant phenomena together. Modern geologists use seismic imaging, satellites, and computer modeling to do just that. Kircher had none of these tools, yet his vision of a dynamic Earth prefigured the holistic thinking that eventually led to plate tectonics.

Kircher presented the Earth as a dynamic body with circulating systems of fire and water. His bold attempt to connect distant phenomena encouraged later thinkers to search for unifying explanations of geological processes. By placing the unseen interior of the Earth within a conceptual framework, he prepared the ground for theories of volcanism and plate tectonics that would follow. His vision of an interconnected Earth endures as a cornerstone of modern geology.

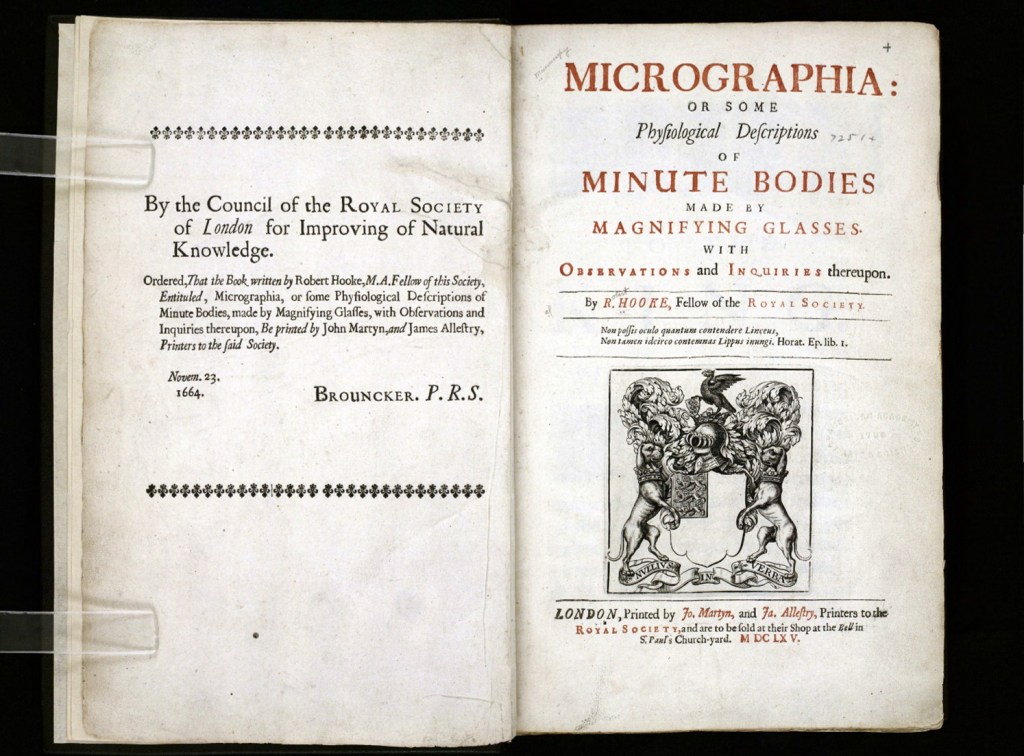

Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665) – The First Great Journey Into the Small

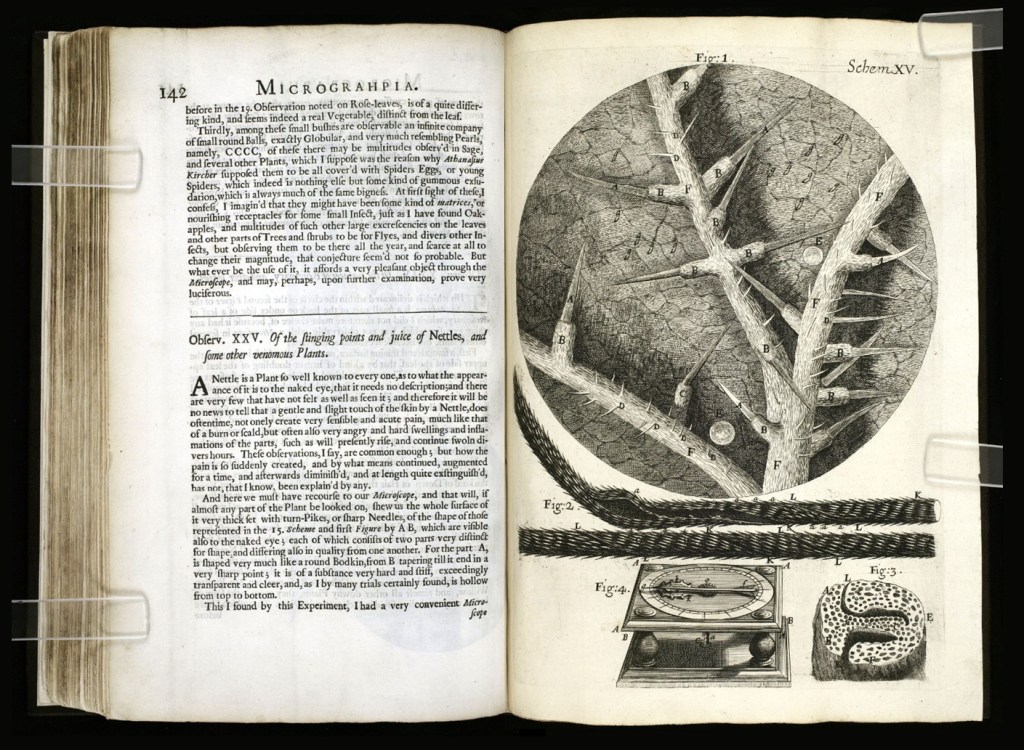

Sixteen-sixty-five was a great year for discoveries. The same year that Kircher produced his treatise on geology (incidentally, also the first year of the first year of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society), Robert Hooke published his famous Micrographia. Hooke had one of the most expansive minds in 17th-century England, a contemporary of Newton (albeit an acrimonious one) and a pioneer in many fields. With Micrographia, he opened an entirely new world to public view. Using a compound microscope, he revealed the hidden structure of the familiar: the armor of a flea, the crystalline form of snowflakes, the delicate veining of leaves.

Turning through the pages of the book, you can almost feel Hooke’s excitement, like a kid with a new toy, using the microscope to peer at anything he could get his hands on. A slip of watered satin, the edge of a razor, some blue mold. And yet he was a serious scientist, carefully outlining methods of experimentation. His decision to publish these images for a wide audience was transformative.

Micrographia astonished readers with detailed images of fleas, snowflakes, and leaves, yet its deeper achievement was to establish microscopy as a serious scientific practice. Hooke demonstrated that instruments could extend human vision into the minute scales of nature beyond human vision. He did for the microcosm what Galileo Galilei had done 40 years earlier for the macrocosm with his 1610 Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger), turning instrumentation to the detailed study of the universe at previously unimaginable scales.

Later generations have built on Hooke’s techniques, using microscopes to uncover the foundations of many branches of modern science, from materials science to molecular biology. The continuing exploration of the microscopic world traces its lineage directly to Hooke’s publication.

Find Out More

Science is always a balance of evidence and imagination to interpret the findings in a new way. The authors of these works (and many others I don’t have space to explore) dared to press against the intellectual and mechanical limits of their time, and in doing so they jostled space for later discoveries. Some of their ideas proved correct, others wildly wrong, but all helped frame the questions that shaped modern science.

The modern books we bring today into Linda Hall’s massive collection will one day be the history of science. One of our responsibilities as stewards of this magnificent repository is to anticipate that future time, when people turn to our collection and ponder what people were thinking about, and studying, in our time. Against that future, we ensure that the Linda Hall Library’s collection will stand the test of time.

If you’re interested in exploring any of these works in greater depth, digital copies of all of these works are available from our online catalog.

Reference

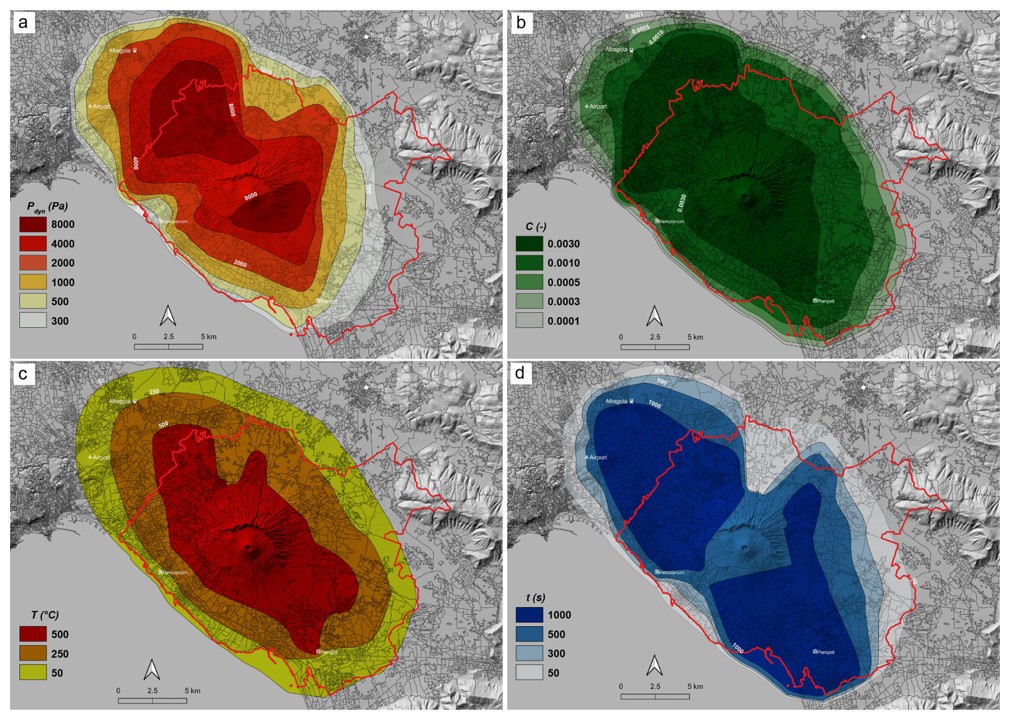

Dellino, P., Dioguardi, F., Sulpizio, R., and Mele, D.: Long-term hazard of pyroclastic density currents at Vesuvius (Southern Italy) with maps of impact parameters, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 2823–2844, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-25-2823-2025, 2025. https://nhess.copernicus.org/articles/25/2823/2025/

Leave a comment