Please imagine Rod Serling’s voice as you read the first paragraph. If you don’t know who that is, shame on you. Watch this clip and come back.

You unlock this door with the simplest of keys: curiosity. Behind it lies another dimension – not of sight or sound, but of neglect. A shadowed space between the bed frame and the floor, where the thick air of forgotten stories mixes with the faint breath of the living. It is a place where the cast-offs of our days gather, and in their gathering, they become something new. You think it only dust. It seems like nothing at all. But step closer, and you’ll find an entire world beneath your feet – quiet, persistent, and very much alive. Tonight’s tale takes us to that twilight realm, the smallest of frontiers, and boldly asks: what, exactly, is that presence beneath your bed?

You kneel down. to do nothing more complicated than to clean beneath the bed. Perhaps you want to banish the ghosts of last winter’s socks, or perhaps find that missing puzzle piece, and there it is: a pallid grey, weightless shape, half fluff and half grit, shifting faintly in the draft of your breath. The light catches it. It seems to tremble. For a moment, you wonder whether dust bunnies are alive.

The question feels absurd until it doesn’t. Every superstition begins with something half-noticed, something that seems to shift when your back is turned. A bat flies from behind a tree. A wolf howls in the distance. Here, in the shadowed underworld of your most important sanctuary – your bedroom – the familiar turns eerily.

You inch closer with the silvery nozzle of your vacuum and in a moment, the thing collapses into nothing, disappearing up the tube to join others of its kind in the belly of your cleaning machine. Have you destroyed a living organism that resented its demise at your hand? Well, no. And yes. It was, in fact, entire microcosm: creatures grazing, hunting, weaving, dying, all within that delicate constellation of lint. These are the true monsters under the bed. They are born of fabric, air, and time, and sustained by skin. Your skin. Rover and Felix’s skin. And Polly’s feathers.

A Brief Under-Bed Natural History

The dust bunny (more prosaically, a “house dust agglomerate”) is not alive in the singular sense. It does not breathe or feed, yet it shelters multitudes or organisms in a complex ecosystem. Metaphorically, it is more planet than creature. Its gravity is static electricity, its continents are skin flakes, and its oceans are humidity. Every home, even the cleanest home (even your home), becomes a universe in miniature. And despite the upcoming Sigourney Weaver film of this name, where something dangerously carnivorous lurks under there, the true story of dust bunnies is infinitely quieter, so much closer, and relentlessly persistent.

What follows is a field guide of sorts, call it a bestiary, of the creatures that live invisibly amongst us, sharing the bounty we unwittingly provide as we go about our daily lives.

Dust Mites (Dermatophagoides spp.)

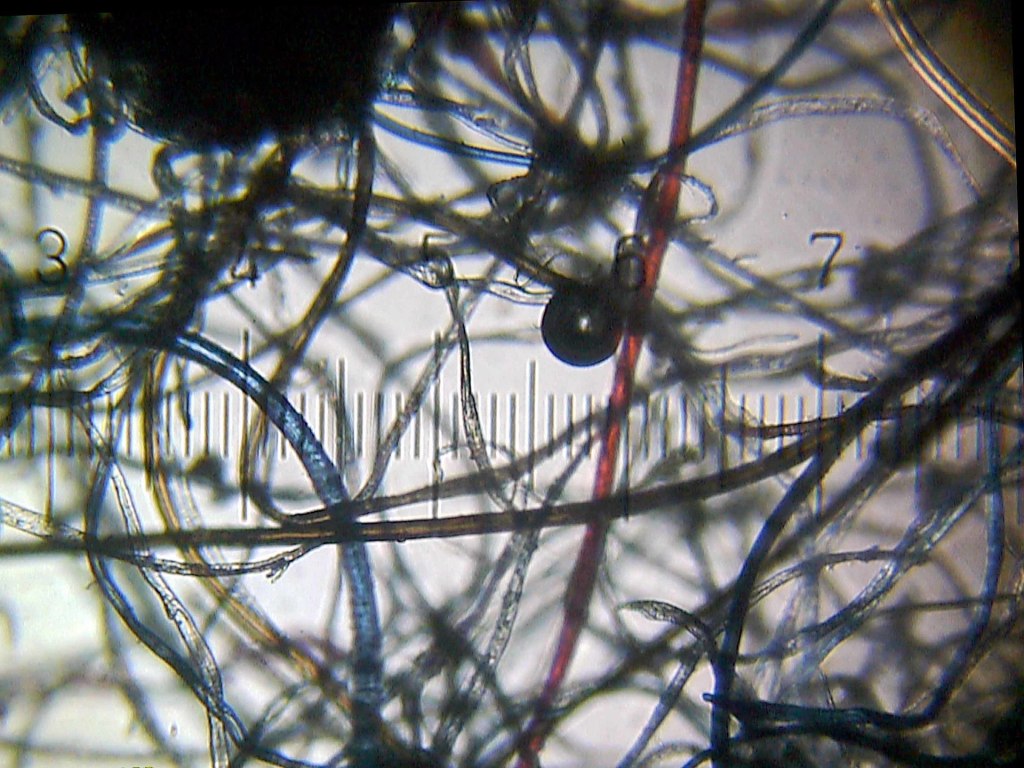

Translucent grazers, no larger than a grain of sand, wandering through the soft valleys of dead skin that fall from us daily. They neither bite nor sting. They simply eat what we shed. Their waste becomes airborne, and when we sneeze, we repay the favor. Evolution has granted them no eyes, no wings, and no concept of irony.

Carpet Beetles (Anthrenus spp.)

The quiet janitors. Adults are almost decoratively round, mottled, the size of a sesame seed, but their larvae are tiny engines of hunger. They graze on anything containing keratin: hair, feathers, wool, the remains of insects. Where light never reaches, they work without pause, reducing our forgotten castoffs to dust.

Booklice (Liposcelis spp.)

Not true lice, but the librarians of decay. They thrive on the faint bloom of mold that rises wherever air stagnates. They are creatures of cellulose and humidity, and their population is the truest measure of how long a room has been still.

Fungi and Spores

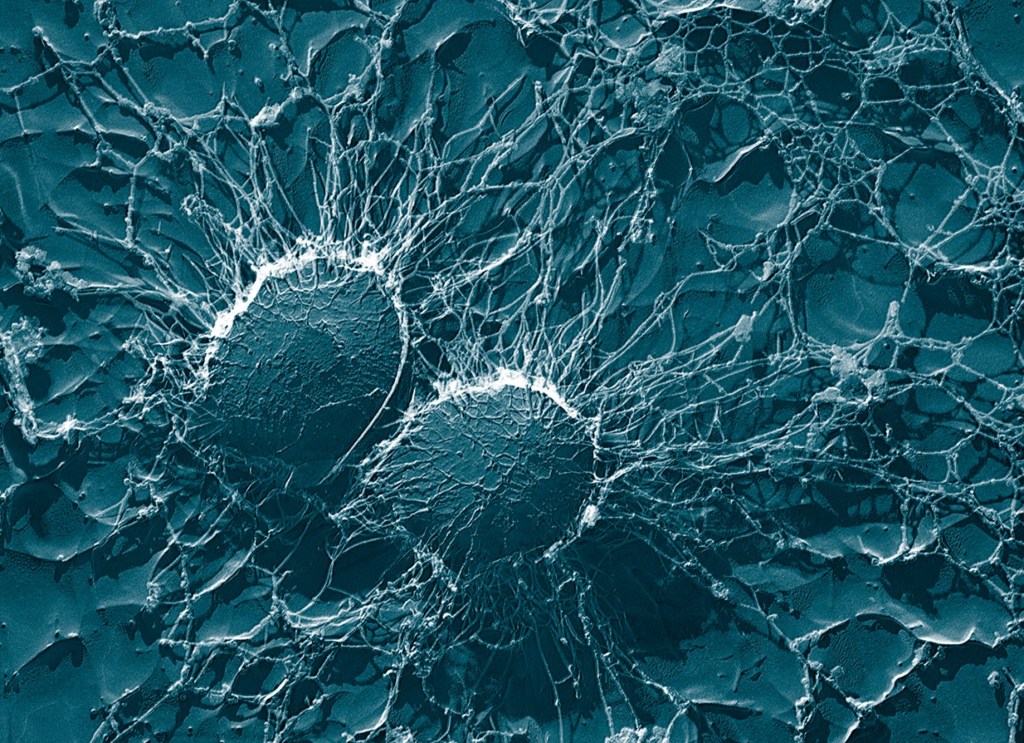

Every breath you exhale carries them. They drift, land, and wait. Under the bed, they find shelter and enough moisture to sprout, enough detritus to digest. Their hyphae stretch invisibly through the lint, binding it together. They are the weavers of the underworld, making filaments where there were none, and binding together their tiny microverse.

Spiders

They live at the top of this minute food chain. They take up strategic residence beneath furniture and the perpetual gloom under your bed is perfect for an ambush predator. To a spider, the world above is too dangerous and here, beneath, they rule unchallenged, feeding on the creatures that graze on your dust. Although you might never thank them, you sleep safer for their presence.

Bacteria

The final inheritors. Invisible, tireless, indifferent. They break down everything that dies in this miniature ecosystem, from a dead mite to a flake of your skin. In their metabolic murmur, matter becomes matter again. It is a kind of resurrection.

Left alone long enough, a dust bunny will evolve something akin to character. What begins as a few rebellious threads, then gathers allies: a hair or two, the husk of a moth, the forgotten fragment of a tissue. Over weeks, these relics twist together, electrostatically bound, tiny arms linked in the gloom, forming eccentric shapes that look as if they might move on their own volition. It is both coral reef and tumbleweed, a tiny savanna alive only in its ability to gather life, always in the process of becoming. Every vibration in the room ripples through their universe. When you walk past in slippers, it is an earthquake. When the cat pounces, it is Ragnarök. And when you finally dispatch it with your Shark Lift-Away, you have become their apocalypse.

Don’t worry. They will return.

Back to Rod Serling…

You have just met the monsters under your bed. They do not come from nightmare, but from the long, patient work of evolution. Their lineage runs deeper than ours, older than the first heartbeat, older than bone. They fed in forests before we walked upright, in caves before we dreamed of fire. Now they feed on us, or rather, on what we leave behind.

They form the base of a small and perfect food web, a quiet empire built from what falls from living things. Mites graze, beetles scavenge, fungi bloom, and spiders hunt. They are the ecology of absence, the life that follows life, drawn to the faintest trace of us.

They are not intruders, only heirs. Yet the intimacy unsettles. For every breath we take, every flake of skin, every forgotten corner is theirs by design. They remind us that evolution never stops watching. It adapts, it persists, it waits beneath the bed.

So tonight, when you turn out the light and the room grows still, remember what shares your shelter. They are older than fear, closer than comfort, and perfectly at home. This is the true lesson of Halloween: the living and the lived-on, together in the dark, bound by the oldest agreement of all.

And somewhere, deep in the quiet machinery of the night, that agreement continues to hold.

Learn more

Barberán, A. et al. (2015) The ecology of microscopic life in household dust. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.1139

Leave a comment