If you’ve been following my occasional explorations of nature’s more eccentric avian performers, you will know I have a soft spot for the absurd. The white bellbird made itself heard with a call louder than a chainsaw. The hoatzin earned its place with an aroma of silage and the juvenile habit of climbing trees with reptilian claws. Now, I bring you another: the club-winged manakin Machaeropterus delicious, a small bird that , on an evolutionary time frame, traded speed, power, and even melody for the ability play a single important note in a highly unique way.

This tiny South American bird, found in the cloud forests of Colombia and Ecuador, is part of a flamboyant family known for dramatic courtship. But the club-winged manakin performs in a way no other vertebrate does. Like a cricket, it plays music with its wings.

Rather than using vocal cords, or even air, the male vibrates two modified wing feathers against each other more than 100 times per second. This act of stridulation, common in insects produces a high, pure tone that cuts through the forest like a single chiming bell. Here’s a link to it on YouTube. Each note is consistent. Every performance sounds the same. And that, as it turns out, is the point.

Structure in Service of Sound

Flighted birds tend to rely on lightweight, hollow bones to reduce gravitational pull. Their skeletons, usually filled with air sacs, are masterpieces of air and strut. However, the male club-winged manakin has a key difference: the radius bone in the wing is completely fused and solidified, trading flexibility for stiffness. This bone, along with the surrounding feather and muscle architecture, supports the rapid vibrations needed to produce sound. It’s an unusual case of sound-driven sexual dimorphism that doesn’t involve singing.

This skeletal reinforcement makes flight awkward for the male. He still moves between branches but cannot fly with speed or distance. Fortunately, he doesn’t need to. Club-winged manakins’ social system keeps them close to home, perched in their small lekking territories, where the performance happens again and again.

The trade-off is evolutionary gold. Dense wing bones allow for stridulation. Stridulation attracts females. Females choose based on the precision and stamina of the tone. And that choice, repeated over countless generations, has transformed the entire upper limb of the male of the species into an acoustic device.

Instruments of Communication

This modification brings to mind another specialist: the woodpeckers (Family Picidae). Their skulls are reinforced to protect the brain from rapid, high-force impacts. But they also use their pecking to communicate, marking territory, attracting mates, and warning rivals through rhythmic drumming. Similarly, and maybe more obscurely, the male palm cockatoo Probosciger aterrimus produces percussive signals during courtship, striking hollow branches with sticks in a kind of avian performance art.

These birds use mechanical sound for social interaction. They belong to a rare class of species that communicate by body (see my recent post on behavioral attractiveness in animals) rather than voice. The club-winged manakin fits squarely in this category. Its feathers act as both plectrum and soundboard. Its skeleton carries the rhythm. And its performance is both display and information, passed from body to body across generations.

Precision, Not Variety

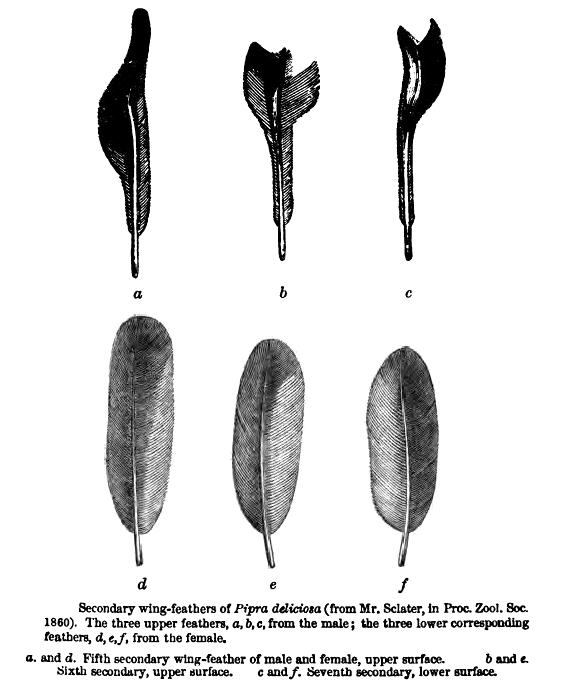

The manakin’s tone sits at about 1500 Hz, a frequency that female manakins detect with ease. (For music lovers, 1500 Hz sits almost exactly between F♯6 and G6, slightly closer to G6, but not quite on the pitch, and just above the top of a flute’s natural range.) The male produces this note using two secondary feathers: one ridged, the other shaped to strike across it. Each wing flick results in several impacts, and the vibration persists briefly after each contact. The result is a sound that conjures more of a rusty gate than anything we associate with birdsong.

There’s no melody, no call-and-response. The note does not change. Females listen for consistency, not complexity. The ideal male produces a stable, clean tone and repeats it precisely, many times, over many hours. The sound must be long enough, loud enough, and pure enough to stand out among competitors. Any deviation could indicate weakness or fatigue. Evolution has made this display brutally simple and the females exquisitely unforgiving.

And so, the manakin practices not variety, but control. His success, and that of his future offspring, depends on his performance being perfectly the same each time.

The Weight of Evolution

Sexual selection favors traits that appeal to mates, even when those traits reduce survival efficiency. The male manakin’s heavy bones hinder flight, but they enable performance. Its feathers are stiff and wear quickly, but they produce resonance. These costs are real. But the benefit is reproductive success. In evolutionary terms, that outweighs nearly everything.

This phenomenon aligns with Darwin’s observations on ornament and excess. He puzzled over the peacock’s tail and the nightingale’s song, both extravagant and costly traits. The club-winged manakin aligns neatly in that tradition. This strategy requires trust in one’s body. The male cannot cheat. He can only perform. And that honesty gives the display its power.

Read More

- Bostwick, K. S., & Prum, R. O. (2005). “Courting bird sings with stridulating wing feathers.” Science, 309(5735), 736. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1113839

- Clark, C. J., & Prum, R. O. (2015). “Resonant properties of feathers produce courtship sounds in the club-winged manakin.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282(1812), 20150976

- Bostwick, K. S. (2006). “Mechanisms of feather sound production in manakins (Aves: Pipridae).” Journal of Ornithology, 147(S2), 153

- Derryberry, E. P., et al. (2012). “Sexual selection and the evolution of song frequency in birds.” Behavioral Ecology, 23(2), 409–417

- Podos, J. (2017). “Animal communication: Mechanical sounds from a musical bird.” Current Biology, 27(6), R202–R205

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “Club-Winged Manakin.” Available at birds.cornell.edu

Leave a comment